This reflection is the second in my four-part Advent series, which seeks to recover the often-overlooked women at the heart of salvation history. I turn initially to Elizabeth, the wife of Zechariah and mother of John the Baptist, who emerges in Luke’s infancy narrative not merely as a passive recipient of divine grace, but as its first articulate witness. Her story draws deeply from the well of Hebrew Scripture, particularly the lineage of barren women – Sarah, Rachel, and Hannah – whose unlikely pregnancies symbolise divine action and covenantal renewal. The Lukan portrayal honours this tradition. Elizabeth’s five-month seclusion after conceiving (Luke 1:24 NRSV) reflects not only a sense of privacy but also an attentiveness to God’s plan for her in her old age.

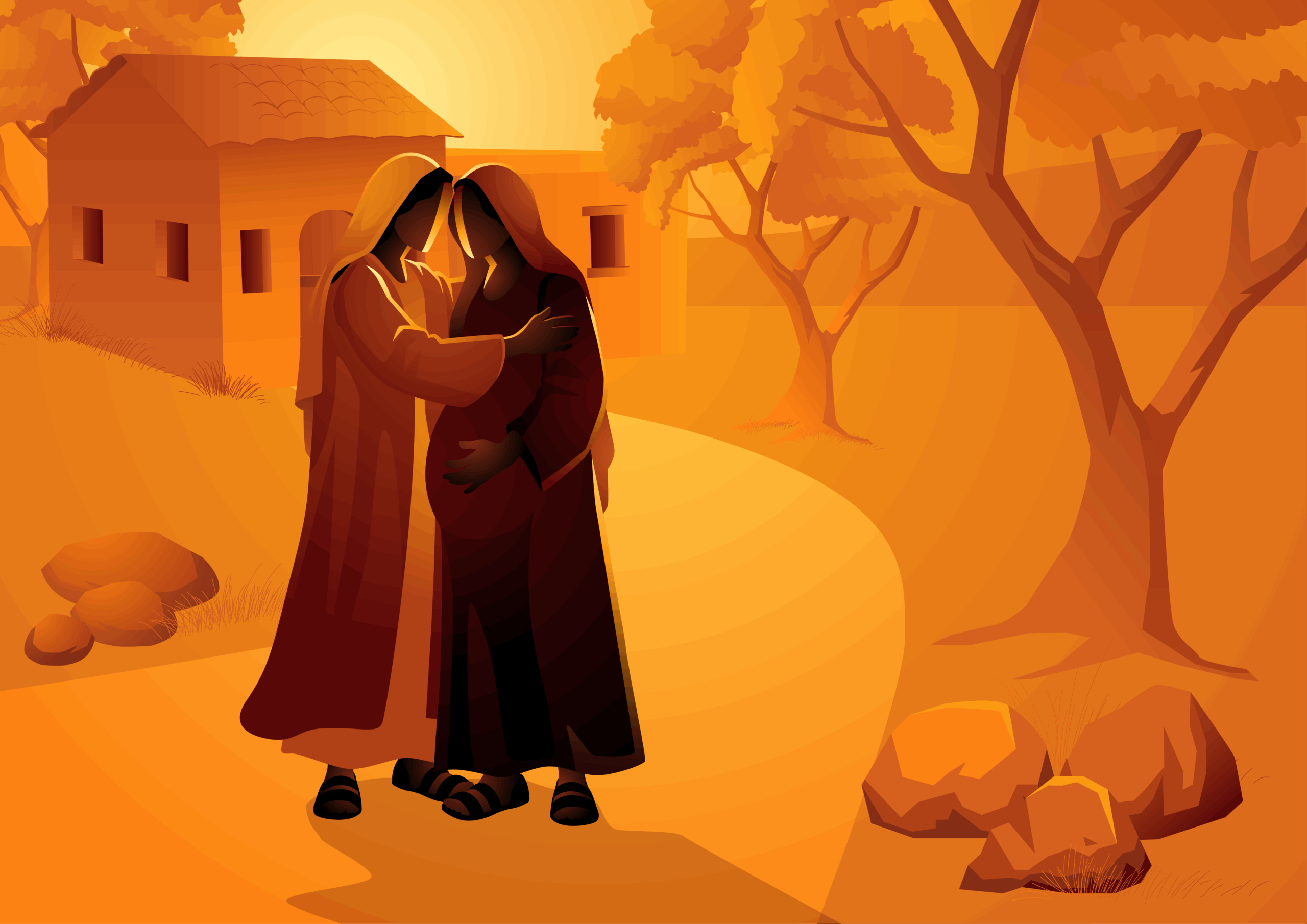

Elizabeth’s spiritual authority when Mary visits her is unambiguous. Her proclamation ‘Blessed are you among women, and blessed is the fruit of your womb’ (Luke 1:42) is more than a familial greeting of warm welcome. Spoken without angelic prompting, it constitutes the first human affirmation of the Incarnation, rooted in maternal recognition. Elizabeth’s joyful words remind us that God’s Spirit is at work not only in future promises, but in present moments of grace. While Gabriel speaks of what John and Jesus will become, Elizabeth celebrates what is already stirring within them. This moment anticipates the Magnificat, and perhaps even inspires it. Elizabeth’s words carry a powerful truth: while the temple priest Zechariah is struck silent, it is Elizabeth, an older woman without recognised authority, who speaks a blessing that shapes the theology of the narrative.

This blessing is spoken from the heart of the home. In recognising Mary’s faith, Elizabeth offers an act of worship, a witness to God’s presence already at work among them. In this way, Elizabeth exemplifies a ‘domestic theology’, one rooted not in temple or law but in shared experience and intergenerational solidarity. Feminist theologians have long argued for the recognition of such informal, relational spaces as loci of theological meaning. They contend that women’s religious experiences often emerge in non-official contexts, challenging patriarchal models of theological discourse. Elizabeth’s voice reminds us that God often chooses to speak through those on the margins, affirming the wisdom at the heart of Catholic Social Teaching: that dignity and moral insight often arise from everyday relationships, not just official roles or institutions. (Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace 2004, n.185).

However, Elizabeth’s story should also be approached with care. In Amoris Laetitia, Pope Francis acknowledges that the inability of some couples to have children ‘can be a cause of real suffering for them’ (n. 178). Elizabeth is not offered to us as a sign that every longing will be miraculously fulfilled. Rather, she stands beside those who know what it is to live with deferred hope, and to carry questions that are not resolved easily. For women and couples today who struggle with infertility, Elizabeth’s journey offers companionship rather than solutions. Her story acknowledges that the path to parenthood, if it comes at all, is rarely simple. For many women today, infertility remains a site of spiritual and ethical struggle. The Church’s rejection of assisted reproductive technologies, including IVF, places women and couples in a complex moral terrain, where longing for a child can coexist with feelings of exclusion and frustration. Elizabeth’s narrative does not resolve these tensions, nor should it be used to promise miraculous outcomes. Instead, her experience – decades of longing and prayer – offers a biblical echo of endurance and dignity in the face of unfulfilled desire. Her later pregnancy, while extraordinary, is not triumphalist; it is quiet, even hidden. This subtlety might speak more powerfully to women today than more spectacular miracle narratives. Elizabeth reminds us that faithfulness is not measured by biological outcome, but by the capacity to hold open space for hope, even in its most tentative forms.

Thus, Elizabeth is not only a theological agent in Luke’s Gospel but also a woman whose witness transcends her historical moment. She embodies a prophetic presence that redefines the boundaries of sacred speech. In Elizabeth’s words and in her waiting, we glimpse a theology of companionship and recognition, one that respects deep longing and reveals God’s presence in the personal moments of women’s lives.

For my next reflection, I follow Luke as his gaze moves from the domestic space of Elizabeth’s home to the sacred temple precincts, where another woman stands as witness. In Anna, we can recognise a theology of endurance that complements Elizabeth’s theology of recognition.

Dr Amelia Fleming is a lecturer in Theology at Carlow College, St. Patrick’s.