Thirty-six years ago, in November 1987, just in time to compete for the highly coveted Christmas No.1 spot in the UK music charts, ‘Fairytale of New York’ was released as a single. Ever since then the song has been enduringly popular and has reached the UK top 20 on 18 separate occasions. It has curiously never reached the top of the charts (although that’s about to change), and it was ‘pipped at the post’ in 1987 by the Pet Shop Boys’ cover of ‘Always on My Mind.’ The song was written by Jem Finer and Shane MacGowan and it features the singer-songwriter Kirsty MacColl on vocals. It was the first single from The Pogues’ third album If I Should Fall from Grace with God. The song captures, with kindness, the fragility of human life and relationships, and it portrays an unflinching picture of addiction, unfulfilled dreams, and damaged relationships. It is, however, the depiction of kindness and love in the song that offers us comfort and hope, and, perhaps, this is why it has remained such a popular Christmas song.

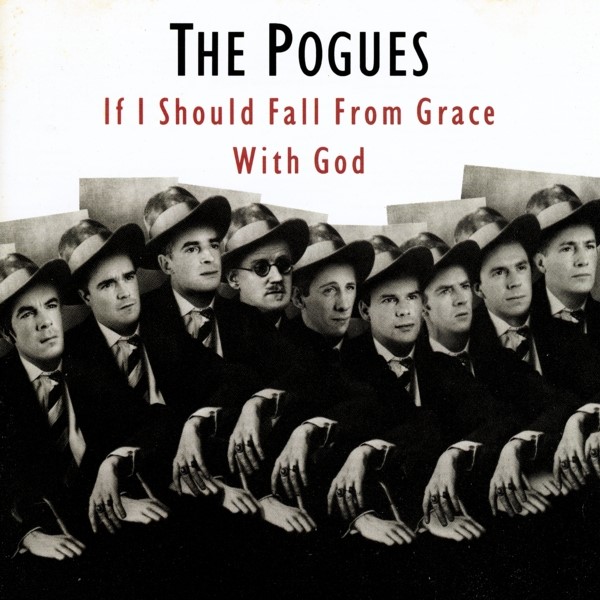

The original cover of the album displayed a photo of nine men (eight of whom are members of The Pogues) wearing the same clothes, facing the same way, and striking the same pose. The ninth member, situated in the middle beside MacGowan, is James Joyce. As Kevin Farrell points out, the album cover playfully suggested that ‘not only is Joyce a Pogue, but The Pogues are themselves a Joycean band.’ Indeed, some scholars have argued that the band saw Joyce as a kindred spirit, someone not unlike themselves with a perceptive ability to lay bare the ambivalences about Irish identity – particularly that of expatiates. In its own bitter-sweet way, ‘Fairytale of New York’ hauntingly captures the dreams and disappointments of so many Irish people who left Ireland in search of a better life.

The song is a tale of an Irish immigrant’s trip down memory lane on Christmas Eve. The singer begins by recalling a night he spend in a New York drunk tank sleeping off a heavy drinking binge. As an old man beside him starts to sing the well know Irish ballad ‘The Rare Old Mountain Dew,’ the singer (MacGowan) begins to dream of, and talk to, his lover:

(MacGowan)

It was Christmas Eve babe

In the drunk tank

An old man said to me, won’t see another one

And then he sang a song

The Rare Old Mountain Dew

I turned my face away

And dreamed about you.

The remainder of the song is a conversation between the singer and his lover about their dreams that never came to fruition. Or maybe it is a conversation he is having with her in his head – after all, as an artist MacGowan has an extraordinary ability to reflect on life from the perspective of being ‘in-between’ worlds. In this song he is an elderly Irish-English expatriate in New York, stuck in a drunk tank reminiscing about his youth with the woman of his dreams. After winning big on the horses, they were optimistic of success but now they cannot find sleep or happiness in a city that no longer has room for them:

(MacColl)

They’ve got cars big as bars

They’ve got rivers of gold

But the wind goes right through you

It’s no place for the old

When you first took my hand

On a cold Christmas Eve

You promised me

Broadway was waiting for me.

The couple’s conversation turns from sugar to vinegar, and we quickly hear of the hard times they went through as a result of their alcoholism and drug addiction as they bicker and reminisce. And yet, almost miraculously, the song ends with love and hope as MacGowan’s character tells MacColl’s that his life revolved and revolves around her:

(MacGowan)

I could have been someone

(MacColl)

Well so could anyone

You took my dreams from me

When I first found you

(MacGowan)

I kept them with me babe

I put them with my own

Can’t make it all alone

I’ve built my dreams around you.

Despite all that they have been through, the couple still have each other on Christmas Day (a lonely day for many expatriates) as church bells ring out and as the police choir sings another Irish classic ballad, ‘Galway Bay.’ Even though they did not achieve their hopes and dreams, the couple still find themselves together for better or worse and, against all the odds, are alive and telling their story to the only people that need to hear it – each other.

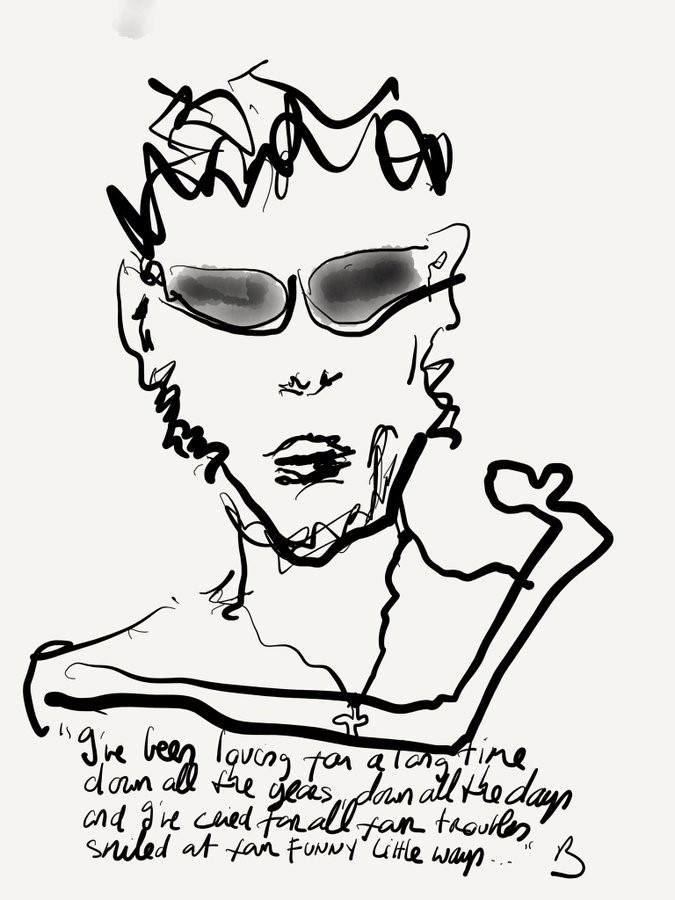

I cannot help wondering why this song has such an enduring popularity (it’s as if it’s not Christmas until we hear it on the radio!) It is, of course, due to MacGowan’s enormous ability to capture so much about the human condition in his songs: desire and excess, love and hate, success and failure. And since his death, so much has been said and written about him and his great gift in this regard. Paul Simon phoned into RTÉ’s Liveline to share his fond memories of himself and Shane, describing him as ‘charismatic’ and as an artist ‘who needed to burn very, very brightly and intensely.’ Tom Waits said that MacGowan’s torrid and mighty voice is ‘mud and roses punched out with swaggering stagger’, while Bruce Springsteen remarked that the passion and deep intensity of MacGowan’s music and lyrics is ‘unmatched by all but the very best in the rock & roll canon.’ And, of course, Bono paid homage via Instagram posting a picture he drew of MacGown featuring lyrics from ‘A Rainy Night in Soho’ with the message ‘Shane’s songs were perfect so he or we, his fans, didn’t have to be.’

Perhaps the most provocative accolade came from Nick Cave who said that MacGowan was a ‘beautiful and damaged man, who embodied a kind of purity, innocence, generosity, and spiritual intelligence unlike any other.’ Cave and MacGowan had a friendship for over thirty years, and they have recorded several songs together – last week Cave played a tear-jerking version of ‘A Rainy Night in Soho’ at MacGowan’s funeral mass in Nenagh. In his book Faith, Hope, and Carnage, Cave talks about his love and respect for MacGowan’s ability to write so compassionately about people’s stories in his songs. He says that he really only understood MacGowan’s writing style after his own teenage son died on a family holiday:

I always heard that kind of compassion in Shane’s songs and his music, and I loved him for it, but at the same time I never fully understood it. The genuine love he felt for people. I never understood it, but I do now. And I believe that is because I became a person after my son died. Not part of a person, a more complete person.

This is an extraordinary and deeply personal statement by Cave about his own story of grief and about MacGowan’s song-writing ability. Through his grief and suffering he became a more complete person. In a similar way, the couple in ‘Fairytale of New York’ are realising who they are and what they have. Through their desires and excesses, dreams and realities, and as they go over and back in their bitter-sweet exchange about the life they have and could have had, there is the tough talk of love and hope which they still have for each other. Indeed, many of MacGowan’s songs perceptively capture the way people deal with their hardships.

Perhaps that is the job of the creative artist – to capture that which is unavoidable in life – to deconstruct, even to dismantle, the known and ‘taken for granted’ self, and re-present it in a new light. After all, we will, all of us, experience some kind of devastation in our lives – if we live long enough! It might be a death, or a relationship breakdown, an illness, or a betrayal. It may be a shattering experience and one from which it feels like there is no coming back. The characters in MacGowan’s songs who go through such devastations, gradually, with the help and love of others, ‘put themselves back together,’ and when they do this, when they ‘begin again,’ they often find that they are a different person. By the end of ‘Fairytale of New York’ the singer (MacGowan) realises that, when all is said and done, it is not his own dreams but the dreams of another, dreams he held close to his own, that have kept him going. The dreams of his lover act as a reality-check in reminding him of what is important at this time of year. Not bad going for a Tipp man!

By Michael Sherman, Lecturer in Theology

Article originally published as: ‘Can’t Make It All Alone…’ Love and Hope in The Pogues, Reality, Vol 95, No. 10 December, 2022 (34 – 38).